Kafka Schema Registry Compatibility Rules

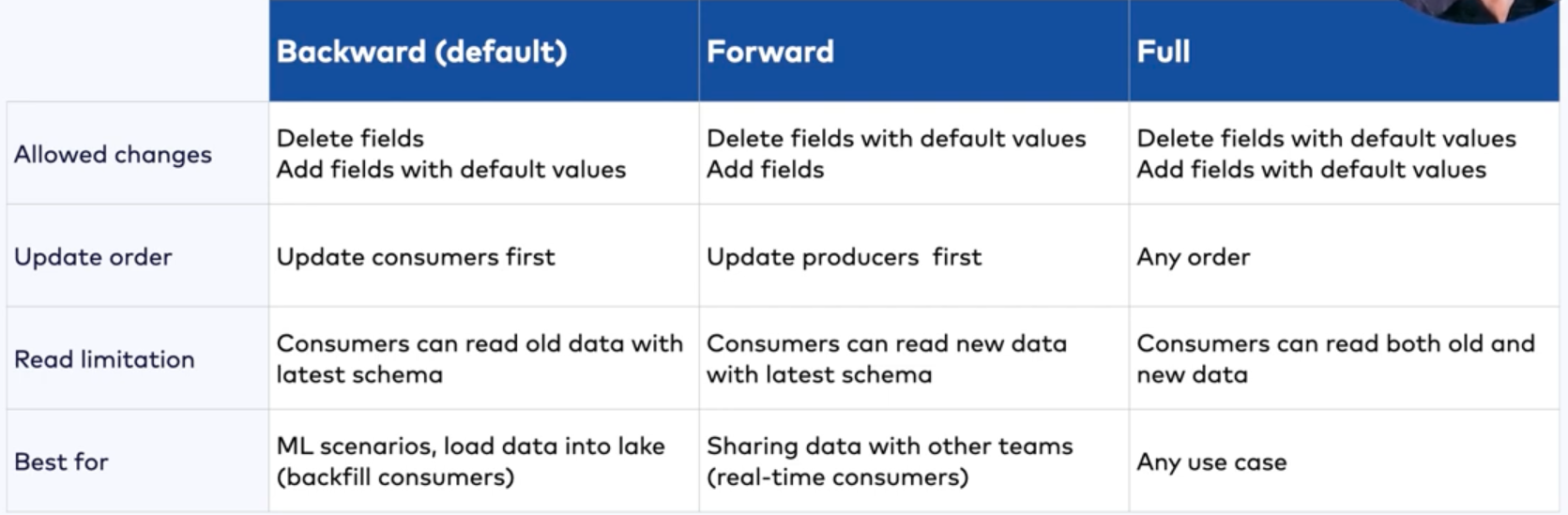

The Schema Registry supports compatibility rules that help manage schema changes gracefully:

- Forward Compatibility: Old consumers can read messages produced with newer schemas.

- Backward Compatibility: New consumers can read messages produced with older schemas.

- Full Compatibility: Both forward and backward compatibility are maintained.

These rules are critical for deciding how changes are rolled out. For instance, if you control the producers and update them first, you might choose forward compatibility, consumers you don't necessarily have control over can be updated at a later date. If you are in control of the consumers instead, backward compatibility ensures they can still process older message versions, as producers are updated progressively (or maybe not at all) by other teams to use the newer schema.

A forward compatibility check can also be thought of as a backward compatibility check with the arguments switched. This implies that a full compatibility check is both a backward compatibility check of the new schema against the old schema and a backward compatibility check of the old schema against the new schema.

When registering a new schema version, compatibility checks can be performed against the previous version, or against all versions. In the latter case, the checks are said to be performed transitively.

The guarantee provided by a compatibility level can be thought of as a safety property. It tries to establish that nothing bad will happen to a client application, depending on how the schema (and therefore the data) evolves over time.

Compatibility checks know nothing of what actual data exists in a system, so may appear more strict than necessary. For example, in JSON Schema, a schema that allows additional properties in the payload that are not defined in the schema is referred to as an open content model. Adding a new property definition to an open content model is a backward incompatible change. That's because undefined properties that appear in old data may conflict with the new property definition, such as having a different type. However, you may not have any data with undefined properties. To get around this issue, the compatibility level can be temporarily set to NONE while the new schema is registered to the subject. Alternatively, compatibility groups can be used, which are explained later.

Compatibility Settings

- Backward - (default) Consumers using the new schema can read data written by producers using the latest registered schema.

- Transitive backward - Consumers using the new schema can read data written by producers using all previously registered schemas.

- Forward - Consumers using the latest registered schema can read data written by producers using the new schema.

- Transitive forward - Consumers using all the previously registered schemas can read data written by producers using the new schema.

- Full - The new schema is forward and backward compatible with the latest registered schema.

- Transitive full - The new schema is forward and backward compatible with all previously registered schemas.

- None - Schema compatibility checks are disabled.

Prefer backward compatibility

Backward compatibility, which is the default setting, should be preferred over the other compatibility levels. Backward compatibility allows a consumer to read old messages. Kafka Streams requires at least backward compatibility, because it may need to read old messages in the changelog topic.

Full compatibility also allows reading older messages but can be overly restrictive, as a full compatibility check is a backward compatibility check of the new schema against the old schema, as well as the old schema against the new schema.

Some argue that full compatibility should be preferred because it allows both new consumers to use old schemas (via backward compatibility) and old consumers to use new schemas (via forward compatibility). With backward compatibility, consumers need to be upgraded before producers, while with forward compatibility, producers need to be upgraded before consumers. Full compatibility allows you to upgrade (or downgrade) consumers and producers independently in any order. However, the actual rules for full compatibility make it restrictive and difficult to use in practice, due to it being a backward compatibility check in both directions.

In general, working with backward compatibility is a more natural means of evolving a system. When making backward compatible changes, we first upgrade consumers to handle the changes, then we upgrade producers. This allows both producers and consumers to evolve over time. When making forward-compatible changes, we first upgrade the producers, but we can choose to never upgrade consumers! This means that the only changes that we can make for forward compatibility are those that won't break existing consumers, which is fairly restrictive.

A better alternative to the use of full compatibility is to use schema migration rules, as described later, which also allows new consumers to use old schemas, and old consumers to use new schemas. Schema migration rules also allow consumers and producers to be upgraded (or downgraded) independently. Furthermore, schema migration rules can handle many more scenarios than a full compatibility setting and were designed for arbitrarily complex schema evolutions, including ones that would normally be breaking changes.

If a schema evolves more than once, you can use transitive backward compatibility to ensure that old messages corresponding to the different schemas can be read by the same consumer.

Understand compatibility groups

Within a subject, typically each schema is compatible with the previous schema. If you want to introduce a breaking change, similar to bumping a major version when using semantic versioning, then you can add a metadata property to your schema as follows:

{

"schema": "...",

"metadata": {

"properties": {

"major_version": "2"

}

},

"ruleSet": ...

}

The name “major_version” above is arbitrary, you could have called it “application.major.version” for example.

You can then specify that a consumer uses only the latest schema of a specific major version.

use.latest.with.metadata=major_version=2

latest.cache.ttl.sec=300

The above example also specifies that the client should check for a new latest version every five minutes. This TTL configuration can also be used with the use.latest.version=true configuration.

Finally, we can configure Schema Registry to only perform compatibility checks for schemas that share the same compatibility group, where the schemas are partitioned by "major_version":

PUT /config/{subject}

{

"compatibilityGroup": "major_version"

}

Use schema migration rules

Once a subject uses compatibility groups to accommodate breaking changes in the version history, we can add schema migration rules so that old consumers can read messages using new schemas, and new consumers can read messages using old schemas. As mentioned, schema migration rules can handle many more scenarios than a full compatibility setting. Below is a set of rules using JSONata to handle changing a "state" field to "status". The UPGRADE rule allows new consumers to transform the "state" field to "status", while the DOWNGRADE rule allows old consumers to transform the "status" field to "state". This means that both old and new producers can continue producing data, and both old and new consumers will see the data in their desired format. Furthermore, producers and consumers can be upgraded or downgraded independently.

{

"ruleSet": {

"domainRules": [

...

],

"migrationRules": [

{

"name": "changeStateToStatus",

"kind": "TRANSFORM",

"type": "JSONATA",

"mode": "UPGRADE",

"expr": "$merge([$sift($, function($v, $k) {$k != 'state'}), {'status': $.'state'}])"

},

{

"name": "changeStatusToState",

"kind": "TRANSFORM",

"type": "JSONATA",

"mode": "DOWNGRADE",

"expr": "$merge([$sift($, function($v, $k) {$k != 'status'}), {'state': $.'status'}])"

}

]

}

}

The following video shows how an old producer and a new producer can both simultaneously interoperate with an old consumer and a new consumer, allowing producers and consumers to be both upgraded (or downgraded) independently, even with a normally incompatible change.

How to Evolve your Schemas with Migration Rules | Data Quality Rules - YouTube

- Migration Rules

- Compatibility Groups

Example Migration Rule

{

"name": "add_fullname",

"kind": "TRANSFORM",

"type": "JSONATA",

"mode": "UPGRADE",

"expr": "$merge([$,{'fullname':firstname & ' ' & lastname}])"

}

Data Quality Rules

- Domain Validation and Event-Condition-Action Rules

- Validates and constraints the values of fields and customize follow-up action on incompatible messages

- Tranformation Rules

- Change the value of a specific field or an entire message (eg. encrypt sensitive fields)

- Complex Migration Rules

- Evolve a schema in an incompatible manner by applying transformations when consuming from a topic to translate the topic data from the old format to the new format

{

"ruleSet": {

"domainRules": [

{

"name": "checkSsnLen",

"kind": "CONDITION",

"type": "CEL",

"mode": "WRITE",

"expr": "message.ssn.matches(r\"\\d{3}-\\d{2}-\\d{4}\")",

"onFailure": "DLQ",

"params": {

"dlq.topic": "bad_memberships"

}

}

]

}

}

Data Contracts

Data Contracts for Schema Registry on Confluent Cloud | Confluent Documentation

Limitations

Current limitations are:

- Kafka Connect on Confluent Cloud does not support rules execution.

- Flink SQL and ksqlDB do not support rules execution in either Confluent Platform or Confluent Cloud.

- Confluent Control Center (Legacy) does not show the new properties for Data Contracts on the schema view page, in particular metadata and rules.

- Schema rules are only executed for the root schema, not referenced schemas. For example, given a schema named “Order” that references another schema named “Product” which has some rules attached to it, the serialization/deserialization of the “Order” object will not execute the rules of the “Product” schema.

- The non-Java clients (.NET, go, Python, JavaScript) do not yet support the DLQ Action.

- JavaScript and .NET do not support schema migration rules for Protobuf due to a limitation of the underlying third-party Protobuf libraries.

Understanding the scope of a data contract

A data contract is a formal agreement between an upstream component and a downstream component on the structure and semantics of data that is in motion. A schema is only one element of a data contract. A data contract specifies and supports the following aspects of an agreement:

- Structure. This is the part of the contract that is covered by the schema, which defines the fields and their types.

- Integrity constraints. This includes declarative constraints or data quality rules on the domain values of fields, such as the constraint that an age must be a positive integer.

- Metadata. Metadata is additional information about the schema or its constituent parts, such as whether a field contains sensitive information. Metadata can also include documentation for a data contract, such as who created it.

- Rules or policies. These data rules or policies can enforce that a field that contains sensitive information must be encrypted, or that a message containing an invalid age must be sent to a dead letter queue.

- Change or evolution. This implies that data contracts are versioned, and can support declarative migration rules for how to transform data from one version to another, so that even changes that would normally break downstream components can be easily accommodated.

Keeping in mind that a data contract is an agreement between an upstream component and a downstream component, note that:

- The upstream component enforces the data contract.

- The downstream component can assume that the data it receives conforms to the contract.

Data contracts are important because they provide transparency over dependencies and data usage in a stream architecture. They also help to ensure the consistency, reliability, and quality of the data in motion.

The upstream component could be a Apache Kafka® producer, while the downstream component would be the Kafka consumer. But the upstream component could also be a Kafka consumer, and the downstream component would be the application in which the Kafka consumer resides. This differentiation is important in schema evolution, where the producer may be using a newer version of the data contract, but the downstream application still expects an older version. In this case the data contract is used by the Kafka consumer to mediate between the Kafka producer and the downstream application, ensuring that the data received by the application matches the older version of the data contract, possibly using declarative transformation rules to massage the data into the desired form.